Rosie the Riveter Delivered Miracles During WWII

By Penny Colman

By the time World War II ended, America’s wartime production record included almost 300,000 airplanes, more than 100,000 tanks and self-propelled guns, 88,000 warships, 370,000 artillery pieces, 47 million tons of artillery ammunition and 44 billion rounds of small-arms ammunition. Time magazine called America’s wartime production “a miracle.”

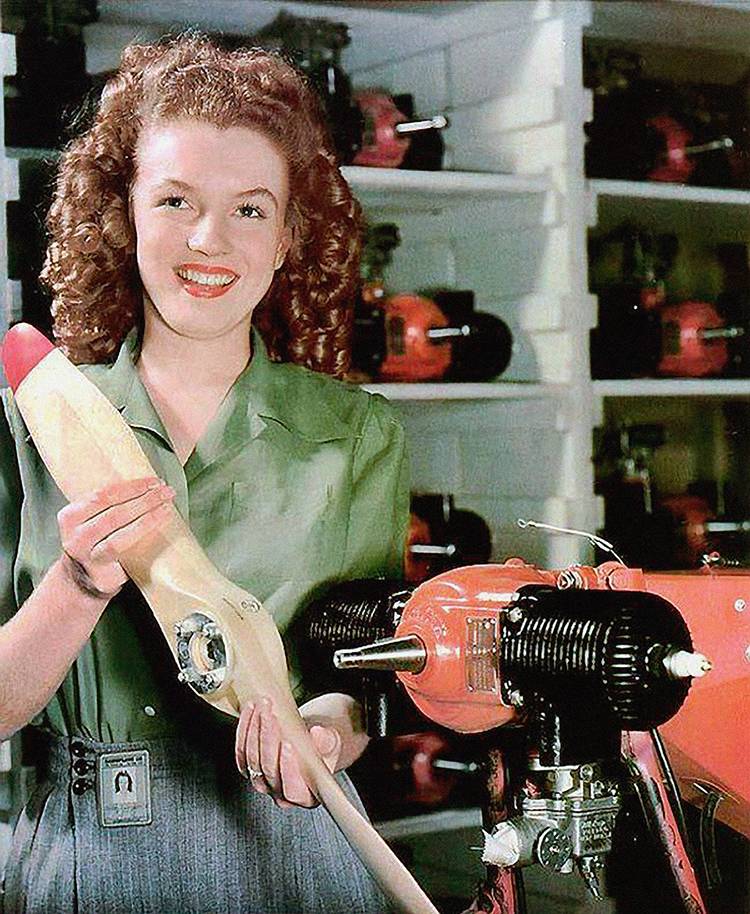

The miracle would not have happened without “Rosie the Riveter.” In real life, Rosie was women like Norma Cutting, a crane operator who worked 60 feet above a cement floor at a steel factory. She was also Norma Jeane Dougherty, who worked at Radio Plane in the dope room where a liquid plastic—or dope—was sprayed over cloth that became the fuselage for target planes and who was photographed by an Army photographer for Yank magazine. Those photographs launched a modeling and film career for which Norma Jeane later changed her name to Marilyn Monroe.

Norma Cutting and Norma Jeane Dougherty were just two of the millions of women who were part of the work force in the defense industry that created the miracle of production. In addition, millions more women performed what were called essential civilian jobs—jobs that kept the home front running smoothly—working as police officers, musicians, loggers, taxi drivers, baseball players, farmers and chemists.

When the war ended in 1945, these job opportunities for women abruptly disappeared.

Norma Jeane Dougherty worked in a Radioplane factory in Van Nuys, California, during World War II. A few years later, she changed her name to Marilyn Monroe and became one of the most famous women of the 20th century. U.S. Army photo

Norma Jeane Dougherty worked in a Radioplane factory in Van Nuys, California, during World War II. A few years later, she changed her name to Marilyn Monroe and became one of the most famous women of the 20th century. U.S. Army photo

WWII Victory Ends Careers

“I will never forget the day after the war ended. We met the girls at the door and we handed them a slip to go over to personnel and get their severance pay,” said William Mulcahy, who supervised women war workers at a factory in Camden, New Jersey. “We didn’t even allow them in the building, all these women with whom I had become so close, who had worked seven days a week for years and had been commended so many times by the Navy for the work they were doing.”

Although America no longer needed women war workers, the story of their wartime contributions is found in the words of people who lived during World War II—in employment records and statistics, magazine and newspaper articles, radio programs and thousands of posters, pamphlets, and photographs. It is an amazing story about a time when stereotypes about men’s work and women’s work were suspended. A time when traditional barriers that had blocked women workers were lowered and they had a chance to prove what they could do.

Let’s stay in touch. Sign up for our emails.

As I studied statistics, read old magazines and newspapers, viewed propaganda films, read oral histories, and talked with former women workers, I was amazed at the variety of jobs women did during World War II. They were barbers, railroad track tenders, aerodynamic engineers, flame cutters, tool machinists, furnace operators, welders, street cleaners, lumberjacks, flag-post painters, drawbridge tenders, and brain pickers in slaughterhouses. I was fascinated by the glut of posters, articles, advertisements, celebrity pitches, movies and songs produced by the government and industry for massive propaganda campaigns aimed at selling war jobs to women—especially housewives—who were also reminded to be “feminine and ladylike, even though you are filling a man’s shoes.”

By the end of 1944, it was clear that the war would not go on much longer. On June 6—known as D-Day—allied troops had invaded France and were pushing the German troops back to Germany. In the war against Japan, U.S. troops had captured island after island in 1943 and 1944. As 1945 began, the peak of industrial mobilization in America was over. **Slowly, the number of jobs in defense industries declined. **Before 1945 ended, millions of men returned from the battlefield to the home front, and soon there were enough male workers again. The propaganda campaigns told women war workers to return to their homes.

Some women were ready to quit.

“As soon as it’s curtains for the Axis, it’s going to be lace curtains for me,” Lorainne Blum, a riveter in a Boeing plant, said in the company newsletter. “I want to establish my own home and stay put.”

Fighting Until the End

But many women did mind losing their jobs. In Highland Park, Michigan, 200 women who had been laid off from the Ford plant conducted a protest. Marching in front of the plant, they carried signs that read “Stop Discrimination Because of Sex” and “How Come No Work For Women?”

When Ottilie Juliet Gattus—who had worked at Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation for the duration of the war—was laid off, she wrote to President Roosevelt, “I happen to be a widow with a mother and son to support. … I would like to know why, after serving a company in good faith for almost three and a half years, it is now impossible to obtain employment with them. I am a lathe hand and was classified as skilled labor, but simply because I happened to be a woman I am not wanted.“

A riveting team works on the cockpit shell of a B-25 bomber at a North American Aviation plant in Inglewood, California in 1942.

As they lived their lives after World War II, many women war workers did not talk about their experience. For some women, it was too painful to remember how quickly their careers as welders, riveters and crane operators had ended. Other women who were working hard to survive did not have time to reminisce. Many women felt people were not interested in their stories, especially in the 1950s, when there was an escalating trend toward blaming working women for problems ranging from juvenile delinquency to divorce.

But women war workers never forgot the experiences that they had for the duration of World War II. They never forgot the thrill of getting a chance to do a job. They never forgot the satisfaction of earning good wages. They never forgot the excitement of being independent. They never forgot that once there was a time in America when women were told that they could do anything. And they did.

-Penny Colman writes about illustrious, but not typically well-known, women and a wide range of significant and intriguing topics in her award-winning books, including "Rosie the Riveter: Women Working on the Home Front in World War II.” A popular keynote speaker, Colman has also appeared on television and radio. Learn more about her latest book at www.pennycolman.com.

More Stories Like This

-

Welcoming WACs, WAVES and SPARs: Serving the Women of WWII at the USO

Step back in history and learn how the USO supported service women during World War II.

-

Rosies Kept America Running During World War II

The “Rosie the Riveter” song first hit airwaves in 1943, but Rosie was already hard at work supporting the war efforts.

-

Over 200 Years of Service: The History of Women in the U.S. Military

From the Revolutionary War to today’s fighter pilots, women have proudly served in the U.S. military for over 200 years. Here is a history of women in the military, and how their roles have changed over time.

Join us in supporting the people who serve by strengthening their well-being wherever their mission takes them.